PARTNER INTRODUCTION

Circular Maritime Technologies

Partner from the start

Circular Maritime Technologies (CMT) was one of the first companies to join the Maritime Remanufacturing Network. We interviewed CMT’s founder and managing director Frank Geerdink to find out more about what this forward-thinking company does. And how its sustainable ship dismantling will complement the future of maritime remanufacturing. Frank’s key words are “circular, safe and competitive”.

“In designing the CMT yard, we are taking humans out of the equation; similar to how car production lines use robots.”

What are the principles of CMT?

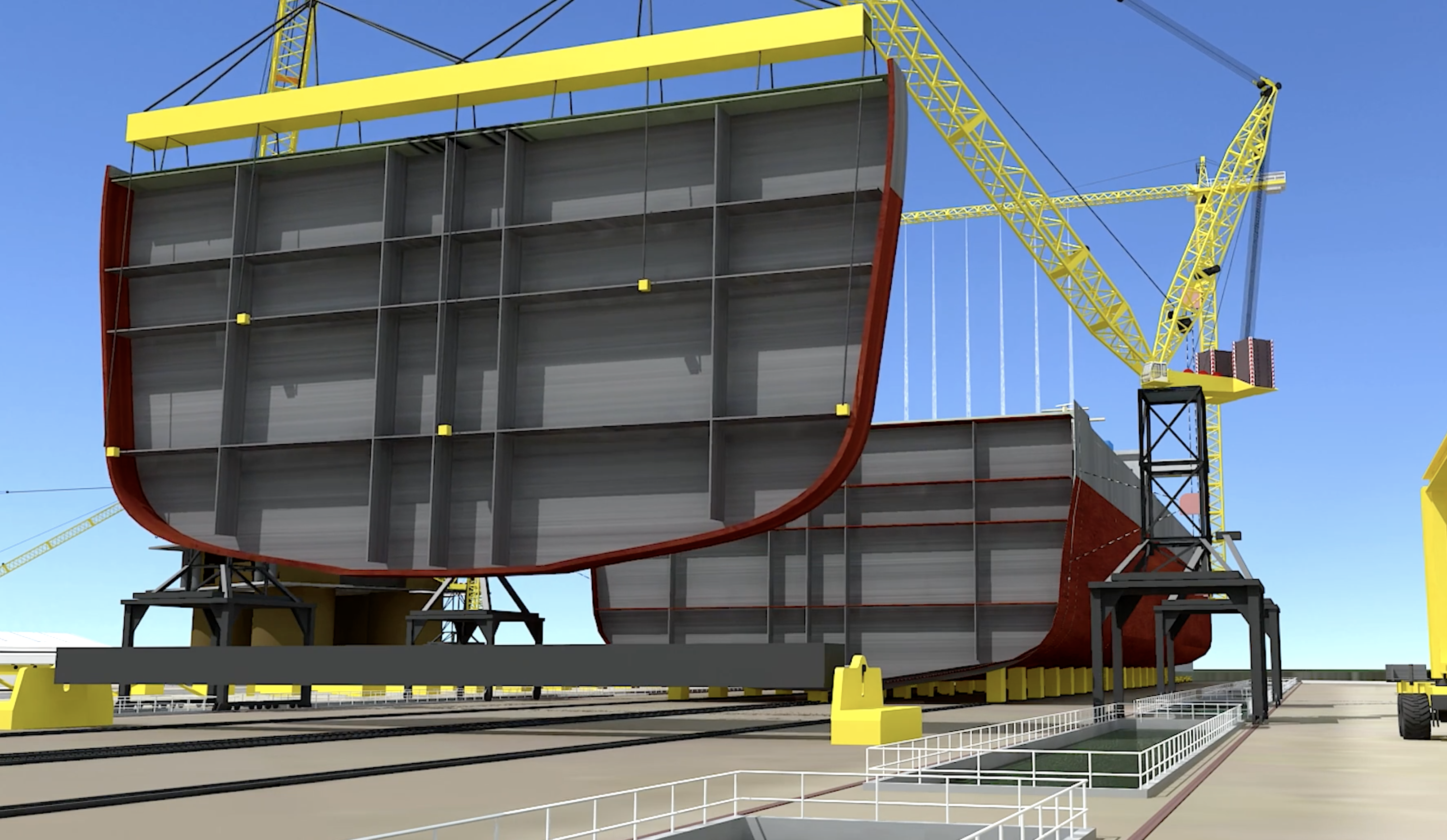

We have been putting together the multiple disciplines that will make a CMT yard operational. This involves adopting existing technologies and combining them in a way that delivers the processes that we require. This is a system that slices a ship into transverse sections and recycles every part of the ship into its original chemical composition; our aim is that not one kilogram of waste will leave the yard. In designing the CMT yard, we are taking humans out of the equation; similar to how car production lines use robots. On a CMT yard, there will not be a single diesel motor in operation; everything will be electric. In fact, for every measurable parameter – whether it’s the environmental or human impact, the quality of scrap steel, the waste water, or legal requirements – we want to score at least a 9.8 out of 10.

Can you tell us about the origins of CMT? And how is this connected to the current situation of shipbreaking on certain beaches in Asia?

The current shipbreaking industry has a hugely negative impact on people and the planet. Currently, over 70 percent of end-of-life vessels are dismantled in Bangladesh, India, Pakistan and China. Most of these ships are ‘beached’ and taken apart manually. This causes severe harm to the workers and the environment. Besides this, you have to look at the financial aspects. Let’s take the example of a 25-year-old, 200-metre-long, 12,500-tonne ship at its end of life. The owner can sell this for scrap for about five million dollars. However, if you look at the total lifetime costs of that ship – which include the original purchase price plus approximately four percent of that price per year in operating costs – this is peanuts. The simple point is that the technology exists to allow us to turn this situation around 100 percent. We have the technology, we have the knowledge and the awareness. The only thing that we are missing is the action.

And this must also be connected to European legislation on ship recycling?

There is one big driver behind the subject of environmentally responsible shipbreaking: legislation. If you own an EU-flagged ship, you have an obligation to have the ship dismantled in Europe. However, there are no facilities whatsoever that can handle ships above 5,000 metric tons. The extent of the problem becomes very noticeable when you look at the fact that in 2030 we will have about 2,000 ships per year that will need scrapping. And by 2040, this number will have risen to 4,000 ships per year. This is why we are aiming to set up the first CMT yard right in the heart of Europe.

“We quickly realised that CMT will have to be able to produce a 100 percent clean, homogeneous, high density steel.”

Who will CMT’s clients be?

At the moment we are in talks with steel companies. This is because of the combined situation where, for the last few years, Europe has been in dire need of high quality scrap steel, and the fact that steel companies want to clean up their ‘environmental’ act. With current methods, scrap steel today is highly contaminated with things like paints, rubbers and plastic. Therefore, we quickly realised that CMT will have to be able to produce a 100 percent clean, homogeneous, high density steel.

When do you expect to have the first CMT yard up and running?

Four years from now, the first yard will be in operation. We have agreements with two parties and a dozen requests from other companies who want to set up a CMT yard. The first yards will be able to handle about 70 ships per year.

Let’s talk about the link between CMT and the Maritime Manufacturing Network.

A ship at the end of its life actually contains many items that are worth more as a product than as scrap. For example, we have been approached by engine manufacturers who are interested in remanufacturing old engine blocks. Also AEGIR-Marine [the founding company of the Maritime Manufacturing Network], they are interested in the potential for remanufacturing components like stern tubes, rudder stocks and propeller shafts.

So a CMT yard would sell these components to the companies carrying out the remanufacturing?

Exactly. Not forgetting that there has to be an economic driver both for CMT and the remanufacturing companies. In addition to closing the circle of ‘product circularity’, we also have to close the circle of ‘economic value’. I see a situation where we have four CMT yards operational within ten years, all having a slipstream of remanufacturing network partners which will scavenge what we are producing.

Isn’t the word ‘scavenge’ a bit negative?

Scavenging is a positive thing. If we didn’t have scavengers in the natural world, we would be stumbling over dead animals all the time. This is how our natural system works. However, from a economics perspective, this is the complete opposite to the traditional Keynesian model, which is defined by constant growth and a linear stream of products, both of which are unsustainable.

How do we develop past this linear stream of production and consumption?

We have to move to a circular stream of products, to really concentrate on the economic benefits of circularity because there is actually a very big economy to be built there. Adapt, adopt and improve: this is what we need to do to achieve this.

More information on www.cmt-international.org